“Not a Throne of Honor, But a Seat of Labor”

A Call for Reformation in ACNA

A Crisis of Governance

As a lay leader and member of an Anglican parish, I write with deep concern about the crisis facing the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA). Several bishops have been accused of mishandling abuse reports, sexual misconduct, and abusing their power. Still others desire the dignity of bishop yet lack the courage to lead when difficult situations arise. These scandals point to a bigger problem: ACNA gives too much authority to individual bishops without enough accountability. Because of this, the church’s structure seems to be tumbling from the top.

Bishops have failed in their duty to shepherd and protect the innocent, and those failures matter. However, focusing only on individual failures misses the point: ACNA’s governance makes these failures likely. We need reform, remembering Augustine’s admonition to bishops that they should lead under the authority of Scripture, be open to correction, and answer to authorities beyond themselves.1

The Pattern Behind the Scandals

Recent failures by bishops show a troubling pattern. Many acted as if their role allowed them to control information, choose whom to protect, and manage the church’s reputation without real oversight. Some bishops sided with accused offenders instead of victims, or the other way around, used discipline against critics, and ignored whistle-blower complaints without proper investigation.

These bishops seemed to act as if their authority made them the final judges of truth in their dioceses. They decided what was credible evidence and who should be heard. But “the good of the church” became more about protecting the church’s reputation than making sure justice was done. As a result, when there are no clear processes or fair investigations, legitimate complaints are dismissed while false allegations destroy reputations.

To be clear, it is not my place to prejudge the outcomes of ongoing investigations into specific bishops. Rather, my concern is with the structural weaknesses that make such crises possible and that harm both genuine victims and those who may be falsely accused. I firmly believe, with the exception of the few in question, ACNA’s bishops are faithful servants seeking to shepherd God’s people well. But even faithful shepherds are poorly served by a model that concentrate too much power in individual hands and provide insufficient accountability.

The Theological Problem

I believe ACNA’s systemic problems flow from unresolved theological tensions. To set itself apart from the Episcopal Church’s liberalism, ACNA focused on strong bishop authority and apostolic succession as signs of true faith. But this led to what seems like a high-church view of bishops as rulers with built-in authority, which does not fit well with Augustine’s vision of bishops as servants accountable to Scripture and the wider church.

ACNA’s own formulary standard challenges this approach. The 39 Articles, Article 21, says clearly: “General Councils...may err, and sometimes have erred, even in things pertaining unto God.” The church must answer to the authority of Scripture, not just to itself. Yet ACNA often acts as if bishops have authority without oversight, which is more akin to later Roman Catholic practice than to the patristic tradition Augustine exemplified.

Biblical Principles for Church Authority

What does the Bible really say about church authority?

Authority is shared. The New Testament often shows groups of elders leading churches (Acts 14:23, Titus 1:5) and councils making decisions together (Acts 15).

Authority is accountable. Peter called himself a “fellow elder” and warned against “domineering over those in your charge” (1 Peter 5:1-3). Paul even corrected Peter publicly “to his face” when he was wrong (Galatians 2:11). If apostles could be corrected, then bishops should be too.

Authority is for service, not control. Jesus made it clear that church leaders should not act like worldly rulers: “The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them...But not so with you” (Luke 22:25-26). Church authority is meant to serve people, not rule over them.

Authority requires more than one witness. Jesus said that serious issues need confirmation from others (Matthew 18:16). Paul applied this rule to accusations against elders (1 Timothy 5:19).

Toward Constitutional Episcopacy

I believe ACNA needs “constitutional episcopacy”: episcopal office preserved but constitutionally limited, liturgically focused but structurally accountable, with presbyters, and even some lay leaders holding equal voice in oversight, investigation, and adjudication of misconduct.

So what should bishops continue to do? They should keep doing what makes their role valuable: shepherding clergy, leading ordinations, organizing mission work, representing the diocese, and teaching the faith.

What should they stop doing? Bishops should no longer act alone in critical matters regarding ethics. They should not discipline people on their own, investigate complaints against themselves or their friends, make major decisions in secret, hide finances, or claim they answer only to God.

At its heart, constitutional episcopacy means moving from behind-the-door decisions to the safety found in an abundance of counselors, consensus on serious matters that Scripture commends (Proverbs 11:14). These changes help everyone: real victims get justice, innocent people are cleared, and the church builds trust through fair processes.

This way of leading has deep roots in Christian tradition. The Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15) included “the church and the apostles and the elders.” Even when James synthesized a conclusion (Acts 15:19), articulating what had emerged from their collective deliberation, the council sent the letter representing the consensus of “the apostles and the elders, with the whole church” (Acts 15:22).

Augustine, guided by Scripture, taught that bishops should lead humbly alongside their fellow clergy and the people, not rule as masters over them.2 Constitutional episcopacy is about returning to historic Anglican teaching: church authority should be shared, accountable, open, and always guided by Scripture.

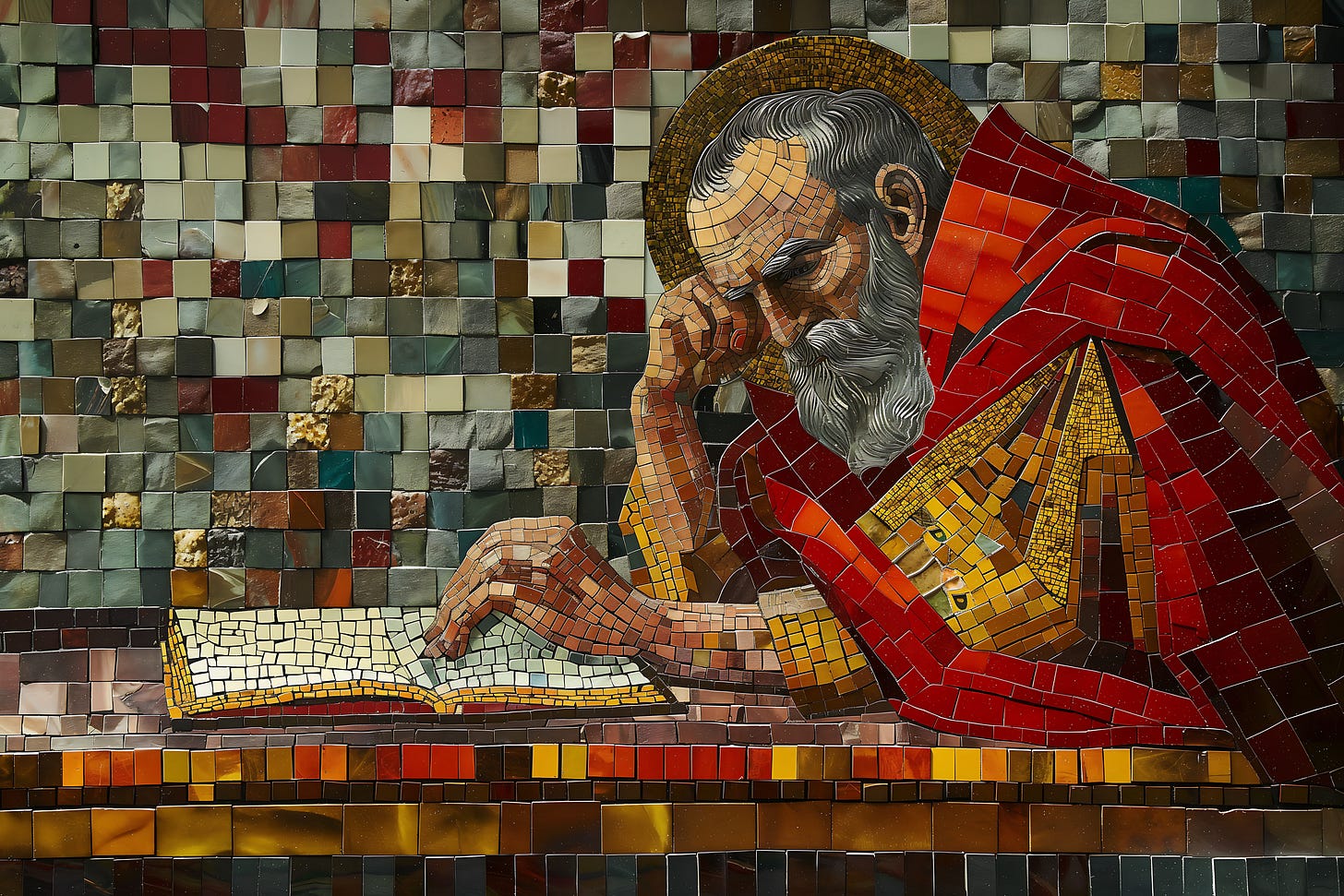

Not a Throne of Honor, But a Seat of Labor

On the anniversary of his ordination as bishop, Augustine preached about the weight and responsibility of episcopal office. “For you I am a bishop,” he told his congregation, “with you I am a Christian; the first means danger, the second salvation.”3 He understood that the bishop’s chair was not a throne of honor, but a seat of labor, a position of service laden with spiritual consequences if misused. His words echo across the centuries to today.

Constitutional episcopacy offers a genuinely Anglican path forward. Bishops can shepherd without abusing their power. And apostolic succession can continue without forming little kingdoms. This approach values both historic order and biblical accountability, preserving what works while reforming what has failed.

These concerns are serious, but not without hope. I’m encouraged by faithful clergy like Rev. Matt Wilcoxen, whose recent article exemplified the courage this moment requires. I’m especially encouraged by Bishop Dobbs, the new Dean of the Province, who has taken decisive action when courage was desperately needed. His commitment to transparency and accountability models faithful leadership. I urge prayer for him and all ACNA leaders navigating this crisis. May God grant them humility to champion reform, courage to establish real accountability, and wisdom to build a church worthy of the gospel we proclaim.

Augustine, Sermon 340, section 1; Sermon 339, section 4.

Augustine, Sermon 340, section 1.

Augustine, Sermon 340, section 1.

Randy thank you for this good word- may it prosper!